Piet Mondrian

Objects, reduced to their most basic lines, sometimes in unearthly color schemes. Lines, perpendicular to each other, diagonally. Planes, diamonds, blocks in primary colors. The result of a search for the essence of life, of man, animal, thing. Gropingly abstracting from the form by omitting more and more things. By constantly reducing details in shape and color, bringing them back to the core. Partly fed by the styles of his time – expressionism, Impressionism – Mondrian (1872-1944) through cubism eventually developed a style of his own. His work shows a life of searching for the one in everything. As a painter he developed in his own unique way and thus laid the first stone for a different, new direction: neoplasticism or the New Imaging [1].

The starting point for this is the earthly, the horizontal as a basis. In his work we see a directed development from the material form to its animating aspect, from the horizontal and vertical principle in the sensory perception to the abstraction of the spiritual. He captures many images from the Zeeland landscape, which was so familiar to him after a few shorter or longer stays in Domburg and the surrounding area. The lighthouse at Westkapelle, the church of Oostkapelle, painted in an unearthly light. All buildings viewed from below, the gaze directed upwards, away from the earthly, the ever-recurring. In his development as a painter, always looking for an inner tension between form and content, until they are completely omitted and he ultimately limits himself to horizontal and vertical, in primary colors and black and white; work that made him known all over the world.

From an early age he was interested in the ideas of theosophy and in 1908 he attended a lecture by Rudolf Steiner in Amsterdam. From a letter to writer I. Querido:

For the time being, at least, I want my work to remain in the ordinary field of the senses, because that is where we still live. Yet art can already form a transition to finer regions: perhaps I wrongly call it spiritual realms, because everything that has form is not yet spiritual, I have read. But it is still the upward path, away from matter.

In a long letter to Rudolf Steiner he explained his views on life and the function of neoplasticism, the New Imaging, in it. Unfortunately, no answer ever came, which hurt but did not discourage him. He remained a member of the Theosophical Society, which he had joined at the age of 37. And he paved the way for a completely new approach to painting [2], an example to many after him. When I see his work I get the impression that he wanted to give an example of what should take place in man himself: striving for the spiritual from the known basis of the concrete-material.

Victor Vasarely

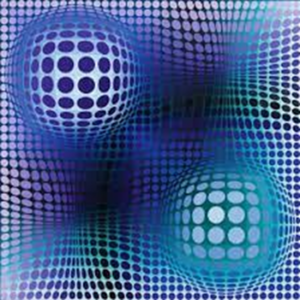

The Hungarian artist Vasarely (1906-997) seems to have continued on the path paved by Mondrian, but he adds another dimension. He brings movement to his works by playing with perspective shifts and curves in lines. He is seen as the founder of Op art and strove for the democratisation of art, with a utopian vision of its public accessibility. When looking at his work, I cannot escape the impression that he was consciously or unconsciously aware that a development of the earthly human being must take place from the form to the essence. Did he possess, like Mondrian, the inner knowing that we are moved by an urge to search for self-fulfillment and lasting happiness, apart from the form and the macabre spatiotemporal play of the opposites? Little can be found about Vasarely, except for an enormous amount of his work.

He must have been busy day and night, so large is his oeuvre, which speaks of a great fascination for lines, movement and optical effect. As if he wants to show that nothing in the form is what it appears to be. Horizontal and vertical lines, grids with sucking depths and convex bulges from which something seems to want to escape. Our soul perhaps, which, trapped in the externalised world, has come to the deep realisation that there must be a way out of this imprisonment?

Victor Vasarely, Feny from homage to Picasso, 1974

Sean Scully

In the work of Sean Scully (Dublin 1945) the influence of Mondrian is undeniably recognisable, albeit in a different way.

It looks like you’re looking at bars, maybe he was in prison?

Diamonds, he seems obsessed with diamonds, he must be of Scottish descent.

These are just a few comments from visitors to one of the exhibitions of his work.

Scully does not say it anywhere in his interviews, but he seems to go his own way, elaborating on the direction chosen by Mondrian. His view of abstract art is absolutely original:

I saw a graffiti text: ‘Time was invented to ensure that everything does not happen at the same time.’ Then I thought: abstract art was invented to make everything happen at the same time. Abstract painting wants to encompass everything and present it as a distilled, mixed and integrated image of everything.

Just as Mondrian spent his entire life distilling the essence from form, Scully mixes and integrates color and material in an endless series of works into a multifaceted oeuvre, thereby simplifying reality into a harmony of lines and planes, horizontal, vertical, diagonal. Sometimes tight, executed with the precision of a ruler, then again in free, spontaneous, sometimes wavy brush strokes, casual even. It expresses a primal force, an all-controlling urge to live. In addition, other work exudes a deep, subdued tranquility. An interaction is entered into with the viewer, who can find himself as a listener, as a resonant object when viewing all this visually overwhelming work. And it appeals on a very individual level. Where as a spectator you walk past one work with an interested but fleeting glance, you notice that for another work you stand looking very long and intensively. You seem to be sucked into it, it sounds clichéd, but it is a real experience. An art critic puts it:

The lines are a kind of tranquil music for the eye, which brings peace amidst the chaos. They are sounding boards for the soul.

Scully himself [3]:

In the late 1970s I noticed that the promoters of abstract art were all extremely sophisticated. Those people were so refined that only they were allowed to enter that refined atmosphere. Then I thought: enough with that nonsense. It is my job to bring abstraction back to the people, to’popularise’ it, without lowering the bar.

Art intended for everyone, as was Vasarely’s ideal.

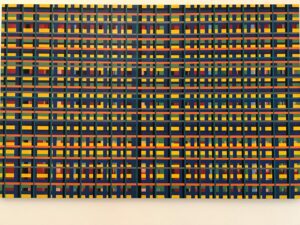

Sean Scully, from the series ‘A dry ocean of stripes’, exposition Villa Panza, Varese, Italy 2019

The series ‘A dry ocean of stripes‘, work from 1969, which he made after a stay in Marrakesh, is an example of abstraction inspired by cultural constraint. Scully:

In the Islamic world, no images of living beings are allowed. So you see stripes everywhere in the streetscape, endless stripes.

As a viewer of his work you cannot escape the stripes, which at first glance can appear as grids. But just blink your eyes and there seems to be depth in it. Different from Vasarely, but still. Intersecting lines, with another grid behind it, and behind that again, behind that again, a stratification like life itself. Which layer is your attention focused on, and which lines, horizontal or vertical, top to bottom, or vice versa, or maybe both? Or at the intersections? You can also see the work as a network of many paths at everyone’s own level of consciousness. Individual horizontal roads, always with a crossroads, with the possibility of a choice: do you continue on the horizontal lifeline – are you and do you remain focused on the material, sensory, the spatiotemporal, with the sometimes unbearable tensions and events associated with it? Or do you choose to focus on the touch of the vertical line of force, on every intersection that presents itself in our consciousness; the vertical that constantly moves us to search and wants to pull us up into the field of life of the unshakable one truth? For there is a very concrete way from the spatiotemporal to the abstract, which is nevertheless so concrete: a field of life where the opposites do not exist. Abstract in the sense of abstracted, released from the material life field of the positive and negative, the one-sided enjoyment alternating with pain and sorrow. Manifested in a new world of unity and love, true Love, which no longer turns into any opposite.

Sean Scully is someone who fought his way to the artistic top after many setbacks. In a later period, when painting had to make way for conceptual art, he managed to hold his own. But wasn’t the heyday of abstract art already over? Didn’t his work come a bit like mustard after a meal, or is his success the result of his assertive marketing? Perhaps we can also see it as a signal, an expression of the circulating nature of the spatiotemporal field of life, in which we are offered time and again an opportunity to learn from our experiences. Over time, a development is visible in the consciousness of every human being and of humanity as an organism. Yet it is the same source of inspiration for everyone that drives the search for true life. Artists such as Mondrian, Vasarely and Scully are an example of inspiration through the vertical lines of force operating in the cosmos and microcosms that, manifesting themselves through the phenomenon of time, touch every human being from that other, new field of life. It is up to us how we respond to that touch. At any moment you can use the freedom of choice and respond to that force that wants to nurture and propel us towards a field of life where all black, white and color merge into Light.

A friend of mine once asked me if paintings could talk, if that was possible. I said, ‘Yes. But with the language of light. Paintings speak with the language of light.’

Scully

Sean Scully ‘Lookin’ outward’, Villa Panza, Varese, Italy 2019

Sean Scully, ‘Happy Days’, Villa Panza Exhibit, Varese, Italy 2019

Sean Scully ‘Crate of air’, Corten steel. Yorkshire Sculpture Park 2022.

Sources:

[1] Pentagram 2018, number 3, ‘The painter at the crossroads’, page 31

[2] Van Paaschen, J., Mondrian and Steiner, Wegen naar Nieuwe Beelding (Roads to New Imaging), Komma 2017, ISBN 9 789491 525322

[3] Niet te stoppen (Unstoppable), artist Sean Scully; https://www.npostart.nl/close-up/21-03-2020/AT_2131932