No one should be surprised about the fact that every time recognizes a contemporary in Hieronymus Bosch (~1450-1516). The small oeuvre of this highly talented artist from the southern Netherlands, often painfully unveils what is of all times: the fear that life inside turns out to be completely hollow, the realisation that everything is desperately temporary, and the knowledge that the human desire for the unbridled intoxication turns us into monstrosities. No wonder that one of the best-known analysts observes:

Bosch is a born pessimist who foresees that God, disappointed at the end of time, closes the Book of Creation!

But is it? This pessimistic conclusion ignores the in a spiritual sense perspectival traits in Bosch’s work. In his often bizarre paintings, the striving of the spirit and the struggle that the seeker has with it in everyday life is also present, in a veiled way, almost everywhere. This has confused many experts. They tumble over each other, as it were. He is said to be a magician, a devout Catholic, an Adamite, a Cathar and a Rosicrucian. Whatever the truth in these, one thing is incontestable: Bosch leads inward. Looking at his works we experience what the famous fourteenth-century Flemish mystic Jan van Ruusbroec once put into words:

What we are, we see; what we see, we are.

Indeed, after a few minutes of observing a work you involuntarily sigh:

Hieronymus, isn’t this about me?

Hieronymus or, as the Dutch call him: Jeroen Bosch, was born as Jheronimus van Aken in 1450 (or 51?) in the southern Dutch town of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, colloquially known as Den Bosch. He would never leave his hometown. With the hot breath of the Inquisition on his neck, he would live and work there until his death on 9 August 1516. Around 1500 he started to use the surname Bosch, after his place of residence. We know little about him. He was a member of the Swan Brotherhood and more than one sentence written by himself has been preserved:

It is a poor spirit that always starts from what has been made up and never from what still has to be made up.

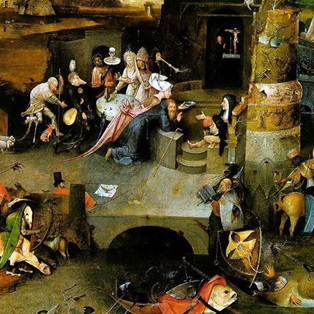

Probably it is meant as the mission statement that master painter Hieronymus Bosch wished to pass on to his pupils. The Swan Brotherhood was a prestigious club of dignitaries, who every Tuesday went to the Vespers in the chapel together and had extensive dinners afterwards. It is remarkable that he was part of the urban, religious lay elite! After all, he rejected ecclesiastical prelates and authorities. We know that for sure when we have a close look at The Temptation of Saint Anthony. There is a priest, adorned with a pig’s snout, reading from a toxin blue magic book, while the inspiration for his sermon is suggested to him by demons.

A swarm of insects leaves his lower abdomen. A hole in his digested robe reveals his true form: a pusy, bleeding skeleton. How is it possible that Hieronymus Bosch was never arrested by the Inquisition? Bosch’s weekly visit to the local brotherhood seems to be a way to maintain himself economically as a crypto-Catholic in his world and to do business It was not that unusual. The Gnostics from the second century up to and including the Bogomils of the fifteenth century also attended all the meetings with the ruling church outwardly, but confessed their true faith and conviction in nocturnal seclusion. And for the latter, Hieronymus Bosch had the peace and quiet of his studio, where he could meet and develop his true being in the silence of his heart.

Come home at last

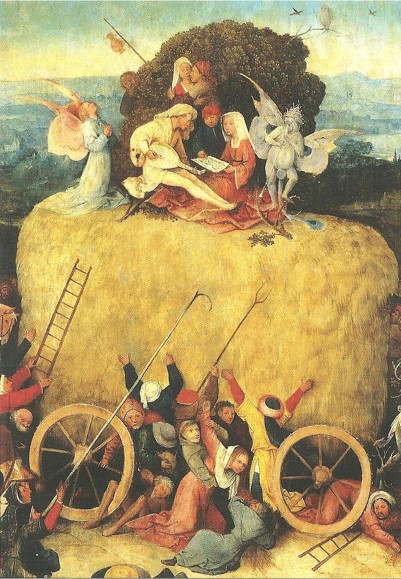

– Now we turn to some works, starting with The Haywain. The world is fundamentally ill, this much becomes clear at first sight. Eva knows that she is naked and looks in bewilderment from the left panel at the haywain. The world as Bosch sees it here is gripped by greed, greed for money and lust.

Hay here means golden money, possession, matter. The authorities follow the haywain seemingly stately, but greedy: the pope on his white horse and the emperor on his brown gelding. Without these greedy people realizing it, their greed ends in hell because the cart is pulled by devils. And in hell on the right panel, they work overtime. There’s a lot of rebuilding and expansion going on. On top of the hay they sing and play the lute. In the thickets a loving couple. The devil, as always present, is wearing the pope’s tiara. And no one takes notice of God, who watches idly… except that one angel!

– On the closed haywain-triptych we find The Pedlar, formerly called The Vagrant or The Lost Son. We see a somewhat weary man, in worn-out clothes with a pack (the back basket) on his back. It looks as though Bosch wants to hold up a mirror to us when we look at the shape of the painting. That look… it seems as though that pedlar is hesitating, we see despair. ‘Am I doing all right?’ he seems to wonder. Behind him we see a whorehouse and an ogling woman. He leans on a stick, moves forward without looking forward. Isn’t that stick – as is often the case – a symbol of faith in himself and in his future? Would the pedlar want to leave his time of earthly debauchery behind?

He is wearing different shoes: one that allows you to go out into the world and one that you put on within the atmosphere of cosy homeliness. ‘Come home at last,’ they seem to say. It must be someone rich in experience, given the greying locks of hair. That pedlar, isn’t that Hieronymus Bosch himself? Isn’t it me? A human being at the crossroads, a pilgrim of life like you and me, a seeker who has taken stock and is now facing a decisive next step.

To be continued in Part 2

Reference:

This article is partly published in Jeroen Bosch, wijsheid-schrijver met beelden, Rozekruis Pers, Haarlem 2016