What is beauty? Is there an objective definition? What is the meaning of the ‘Golden Ratio’? Does beauty have a deeper origin?

It was cold and rainy. The imposing Tyrolean mountains hidden behind a veil of low-hanging clouds seemed nonexistent. How nice that a field trip on Modern Alpine Architecture included well-known architects.

We met in a small village in Vorarlberg, Austria, and discussed the concept of beauty in architecture. Opinions about what was ‘beautiful’ were broad, and one participant mentioned the Golden Ratio. In earlier times and well into Antiquity, the Golden Ratio was inextricably linked with architecture as the basic measure of the artistic value of a building. In urban planning, ground plans bore witness to a higher knowledge, indicating harmony with the soul.

Other participants objected since today buildings are no longer built this way. The concept of beauty is subjective. No sooner said than we reached the village square, the sun came out for a short time from behind dense clouds and illuminated the scenery. Beautiful historic buildings of traditional Alpine architecture lined a group of lime trees, with a small church in the middle. The square was artfully paved.

Participants were speechless at first and then unanimously commented on the beautiful, harmonious ensemble of this village square, where everything was well-proportioned and in the right place. The language of architecture had directly touched their hearts. What exactly led to this change of mood?

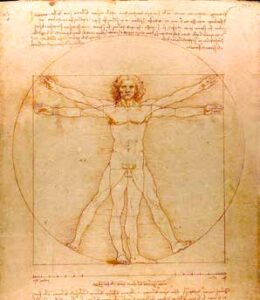

The group spontaneously opened up to the essence of the Golden Ratio, and a lively conversation ensued. The Golden Ratio can be described as the basic measure of ‘sacred geometry’[i] which consists of harmonious proportions that also underlie the ‘architecture’ of the human being and the ‘microcosm’, as an image of the cosmos. The Vitruvian Man is the famous drawing by Leonardo da Vinci where the average proportions of the human body differ only slightly from the Golden Ratio.

What is the Golden Ratio? It is the unique division in which the relationship between the whole and the part is preserved. The whole is in the same proportion to the larger part as the larger part is to the smaller part. Another term used in the past was ‘divine proportion’. This was intended to express the connection between creation, the divided, and its divine origin, the whole.

Fig. 1: Leonardo da Vinci, the Vitruvian Man

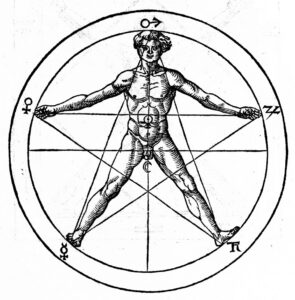

Man was also depicted in a pentagram. The five-pointed star also exhibits the geometry of the Golden Ratio. This means that man was created in accordance with divine proportions.

Fig. 2: Man depicted in a pentagram. After Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486–1535).

This measure exists on a large scale in the geometry of the universe, e.g., in the shapes of galaxies, and on a smaller scale in the shapes of the mineral, plant, and animal kingdoms.

Fig. 3: The petals of roses and other plants grow at the ‘Golden Angle’ (iStock, processed by Uwe Döpel).

Where does the Golden Ratio appear in human civilisation? This synthesis of craftsmanship and art was present in almost all cultures in the past and can still be marvelled at today in the Orient. There is no separation between the two. The word ‘architecture’ etymologically means ‘first art’ or ‘original art’. The expression ‘arts and crafts’ is already evidence of a break in the relationship between art and ‘normal’ craftsmanship; form and function became separate, with the functional coming to the foreground.

Fig. 4: A classic example of the Golden Ratio in architecture is the Parthenon in Athens (photo: iStock, processed by Uwe Döpel )

Fig. 5: Moroccan arabesques. Perfect geometry according to the Golden Ratio (photo: Uwe Döpel)

With the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century beginning in Europe and spreading worldwide, there was an ever-faster development of mental consciousness and, at the same time, increasing materialism. Applied to the relationship between body, feeling, and mind, the tendency is towards the development of a top-heavy person who is characterised by a logical-rational mind and increasingly threatens to lose touch with the heart and emotional world.

The ‘voice of the heart’ as the epitome of beauty and love is increasingly being ignored by the intelligence of the mind. This is expressed, among other things, in a predominantly functionally oriented architecture. It is in the process of losing the connection to its origin in ‘divine art’.

Fig. 6: Functional modern architecture in contrast with traditional architecture (Photos: Uwe Döpel)

Is beauty only a question of proportions? Are there other, deeper aspects and dimensions? Think of a consciousness of simplicity which has left the self-centred perspective, a selfless simplicity which has no goal and does not want to own anything. It can refer to a created form – or not.

If we seek the beautiful to enrich ourselves and avoid the ugly, we lose an important aspect of true beauty. In the words of Jiddu Krishnamurti[ii]:

‘When we are without love, we create a civilization in which the beauty of form is sought.’

So addiction to external beauty can be a consequence of an inner void. On the other hand, beauty in the outer world can be an expression of inner beauty. It can be a projection of the original divine beauty into the dual outer world.

What then is our reality? Reality is an effect of our outward-looking consciousness made up of thoughts, feelings, and will, which, only through projection outwards, can be experienced and reflected. If the ego wants to possess beauty, it creates a ‘red whirlwind’ of desire that clouds unity with the inner core and creates a duality: the ‘ugly’.

Don’t we need a contrast between the beautiful and the ugly, between light and shadow, to nurture our longing for true beauty? Is true beauty only recognisable by contrast with the ugly?

Beauty can be perceived without wanting to be devoured, possessed, and experienced again and again. If you succeed in just looking at beauty, then there is no pain or fear of losing it. Beauty has then fulfilled its mission. It has brought the observer to silent wonder. Beauty on the outside can then be reflected in an indescribable beauty on the inside. The soul can merge with beauty, since it is no longer on the outside. Observer and observed become one, experiencing their essence as one. The soul leaves separation and flows back into unity. There is healing, and there is love.

When one understands the deep meaning of the desire for healing and of this unfulfillable longing, an incredible joy in life can unfold: the joy of the ‘beautiful spark of the Gods’[1]. This joy lies beyond thinking. It is a quality of true love and can only be perceived in the here and now.

As Krishnamurti puts it (ibid.):

‘You cannot have love without beauty. Beauty is not something you see – a beautiful tree, a beautiful picture, a beautiful building, or a beautiful woman. Beauty only exists when your heart and mind know what love is. Without love and this feeling for beauty, there is no virtue.’

When I think back to the excursion with the architects, and the moment when we were all united in the shared feeling of beauty at the village square, there seemed to be a unifying intersection of all that is individual and subjective. The Golden Ratio and Sacred Geometry are a signature of divine beauty like Ariadne’s thread, that leads us out of the labyrinth of the duality of good and evil, of beauty and disharmony, to the true beauty of our inner divine being. The more we turn to it, the more the labyrinth dissolves.

The point of duality is for man to recognise his true self. It is one with the essence of God. The futility of finding undivided beauty and true contentment in a dualistic world is part of the essential self-knowledge of man.

Faust says:

‘If I will say to the moment: linger, you are so beautiful! Then you may bind me in chains, then I will gladly perish!’

Everything Faust had experienced was unable to make him truly happy. He was deeply imbued with the knowledge of the transience of earthly beauty. The tragedy with Gretchen and the encounter with Helena, with whom he wanted to unite happiness and beauty, were of particular importance in this respect. Through the fire of purification, Faust finally becomes insensitive to external sensory stimuli represented by his blindness[iii]and open to the beauty of the inner light.

‘The night seems to penetrate deeper and deeper, but within shines a bright light.’

[i] Cf. Kükelhaus, H. (2001): Urzahl und Gebärde. Grundzüge eines kommenden Maßbewusstseins (Foundations of an Emerging Awareness of Measure), Klett and Balmer Publ. House, Zug

[ii] Krishnamurti, Jiddu (2021): Vollkommene Freiheit (Complete Freedom), 11th edition, Fischer Taschenbuch

[iii] Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Faust, The Tragedy Part Two